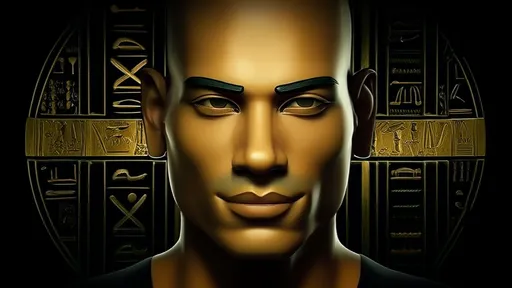

The sands of time have long obscured the faces of Egypt's ancient rulers, but modern science is now peeling back the layers of history in an unprecedented way. The reconstruction of pharaonic DNA has opened a revolutionary window into the past, allowing researchers to visualize the literal faces of power that once commanded the Nile Valley. This groundbreaking work transcends traditional archaeology, merging cutting-edge genetics with forensic artistry to resurrect visages frozen in time.

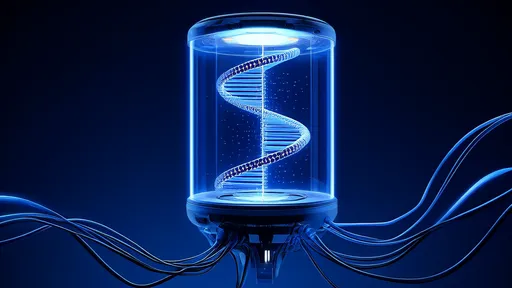

Deep within the bone marrow of mummified remains, geneticists are extracting degraded DNA strands that hold the blueprints of royal lineage. These fragile molecular fragments, some over 3,000 years old, require delicate handling and advanced sequencing techniques to piece together the genetic puzzle. The process resembles solving a billion-piece jigsaw where half the pieces are missing—each recovered segment bringing us closer to understanding the biological reality behind the golden death masks.

Forensic artists working with anthropologists now employ a remarkable synthesis of science and art. By mapping genetic markers for skin pigmentation, hair texture, and facial structure onto 3D cranial models, they're creating the most accurate reconstructions ever attempted. The resulting portraits show rulers not as idealized god-kings of temple reliefs, but as living, breathing individuals with distinctive features passed down through their DNA.

The recent facial reconstruction of Ramses II caused particular astonishment in archaeological circles. Contrary to his monumental statues depicting an archetypal strong-jawed ruler, genetic analysis revealed a prominent nose structure and unexpectedly red hair—a trait potentially inherited from distant European ancestors. Such discoveries challenge long-held assumptions about the homogeneity of ancient Egyptian royalty and suggest complex dynastic interconnections across the Mediterranean.

Beyond mere physical appearance, these genomic studies illuminate previously unknowable details. Pathogens preserved in dental pulp have identified diseases that plagued the pharaohs, while isotopic analysis of bone collagen reveals surprising dietary habits. One particularly intriguing finding shows several 18th Dynasty rulers had genetic markers for obesity—a stark contrast to their typically depicted slender forms in tomb paintings.

Ethical considerations shadow these scientific triumphs. The very concept of disturbing royal remains for genetic analysis would have horrified the ancient Egyptians, whose entire cosmology centered on preserving the physical body for eternity. Some scholars argue that such research, while academically valuable, violates the spiritual intentions behind mummification. Others counter that understanding these rulers as biological entities rather than mythological figures enriches our connection to shared human history.

Technological limitations still present significant hurdles. The hot Egyptian climate and ancient embalming techniques have degraded most DNA beyond readability, leaving only select well-preserved specimens viable for study. Contamination from centuries of handling and earlier archaeological methods poses additional challenges, requiring painstaking procedures to isolate original genetic material from modern interference.

As methodology improves, researchers anticipate reconstructing entire dynastic family trees through shared genetic markers. Already, unexpected relationships between presumed unrelated pharaohs have emerged, rewriting succession narratives carved in stone. The famous boy king Tutankhamun's genomic portrait not only revealed his malaria-weakened constitution but confirmed his parentage through DNA matching—settling century-old debates in Egyptology.

This fusion of molecular biology and historical study represents more than academic curiosity. By giving faces to names known only from hieroglyphs, the work bridges the vast temporal divide separating modern people from ancient civilizations. The reconstructed visages serve as powerful reminders that these were not abstract historical figures, but flesh-and-blood humans who laughed, ruled, suffered, and shaped one of history's greatest civilizations.

The implications extend beyond Egyptology. Similar techniques are being adapted to study other ancient cultures from the Incas to Chinese emperors, creating a new interdisciplinary field some call "molecular archaeology." As databases of ancient DNA grow, scientists may eventually trace the migration and mixing of royal bloodlines across continents and millennia.

Public fascination with these genomic portraits has reached unprecedented levels. Museum exhibitions featuring the reconstructed faces consistently draw record crowds, while television documentaries bring the science to millions worldwide. This popular engagement demonstrates humanity's enduring hunger to connect viscerally with the past—to look into the eyes of history and see something recognizably human staring back.

Critics within the scientific community caution against overinterpretation. DNA can indicate probable physical traits, but environmental factors and the subjective nature of facial reconstruction leave room for error. The golden death mask of Tutankhamun, for instance, presents an idealized version that likely differed from his living appearance. Researchers emphasize these reconstructions represent scientifically informed approximations rather than photographic accuracy.

The next frontier involves moving beyond static facial reconstructions. Pioneering teams are experimenting with animating these ancient faces using muscle modeling software derived from forensic science. Early tests have produced startlingly lifelike simulations showing how a pharaoh might have smiled or frowned—an eerie experience that further collapses time between the modern viewer and the ancient subject.

As the technology progresses, ethical questions multiply. Should we recreate the faces of all historical figures whose remains we possess? What responsibilities do scientists have toward descendant communities? The debate grows more complex as private companies begin offering ancestral DNA services that promise to reveal customers' "inner pharaoh," commercializing what began as pure academic inquiry.

What remains undeniable is how these genomic portraits have transformed our relationship with antiquity. The mummies no longer lie silent in their sarcophagi—through their resurrected DNA, they speak across millennia in the universal language of human biology. In their reconstructed features, we see not just rulers of a lost civilization, but our shared humanity preserved against all odds in the double helix of life itself.

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025