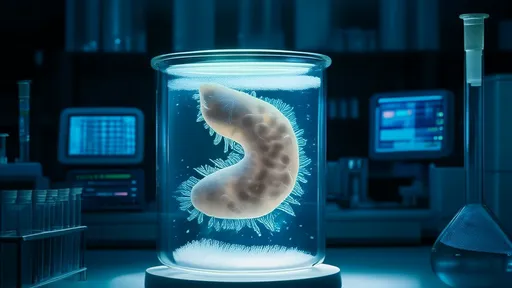

The discovery of Ötzi the Iceman in 1991 provided an unprecedented window into Neolithic life, but recent breakthroughs in molecular archaeology have revealed even more astonishing details about his final hours. Scientists have now successfully reconstructed the stomach contents of this 5,300-year-old mummy, including a remarkable molecular-level recreation of his gastric acid environment at the time of death.

This groundbreaking research represents the first time researchers have been able to chemically recreate the stomach conditions of an ancient human. The team working on the project developed innovative techniques to analyze the minute chemical traces remaining in Ötzi's preserved digestive system, allowing them to determine not just what he ate, but how his body was processing those final meals.

The study began with a comprehensive re-examination of the Iceman's stomach contents using advanced mass spectrometry and protein analysis techniques. While previous studies had identified the broad composition of his last meal - wild goat meat, einkorn wheat, and traces of toxic bracken fern - the new research went much deeper, analyzing the molecular byproducts of digestion that revealed the precise acidity levels in his stomach.

What emerged was a startlingly complete picture of Ötzi's gastrointestinal state in his final days. The acidity levels suggested he hadn't eaten for several hours before his last meal, followed by what appears to have been a large, hurried consumption of food. The chemical markers indicate his stomach was working vigorously to digest this meal when he met his violent end.

Perhaps most fascinating was the discovery of intact pepsin molecules - digestive enzymes that only function in highly acidic environments. These fragile proteins had survived millennia thanks to the unique preservation conditions of the glacier. Their presence allowed researchers to calculate that Ötzi's stomach pH at death was approximately 1.5, slightly less acidic than modern humans but well within normal ranges.

The research team then took the extraordinary step of recreating this ancient gastric environment in the laboratory. Using the chemical profile derived from Ötzi's remains, they synthesized an artificial "Iceman stomach acid" solution and tested how it broke down samples of the same foods found in his stomach. The results provided unprecedented insights into Neolithic digestive processes.

One surprising finding was the efficiency with which Ötzi's stomach acid broke down the tough muscle fibers of wild game. The recreated gastric environment dissolved ibex meat samples significantly faster than modern stomach acid would, suggesting possible evolutionary adaptations to a hunter-gatherer diet high in lean wild meats.

The bracken fern traces in Ötzi's stomach have long puzzled researchers, as this plant is known to be toxic. The new gastric recreation helped solve this mystery - the fern's harmful compounds broke down differently in Ötzi's stomach chemistry compared to modern humans. This suggests he may have been using it medicinally rather than consuming it as food, with his stomach environment providing some protection against its toxicity.

The implications of this research extend far beyond understanding one ancient individual. The techniques developed could revolutionize our knowledge of ancient diets, health, and even the co-evolution of human digestion with changing food sources. By comparing Ötzi's gastric chemistry with modern populations, scientists hope to track how human digestion has adapted to agricultural diets over millennia.

This molecular reconstruction also offers new perspectives on Ötzi's final journey. The combination of partially digested food and stomach chemistry suggests he ate a large meal while on the move, possibly fleeing from attackers. The presence of undigested muscle fibers indicates he was killed before his stomach could complete its digestive cycle, providing a grim but precise timeline of his last hours.

Future applications of this technology could allow researchers to reconstruct the stomach environments of other well-preserved ancient humans, from bog bodies to desert mummies. Each could provide unique insights into how different ancient cultures processed their food and what this reveals about their lifestyles, health, and evolutionary adaptations.

The Ötzi stomach reconstruction stands as a landmark achievement in archaeological science, blurring the lines between past and present in ways previously unimaginable. As one researcher noted, "We're not just learning what was in his stomach - we're learning how it felt to digest a meal 5,300 years ago." This intimate connection with our ancient ancestor's bodily experiences offers a profoundly human perspective on the past.

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025